Negative outlook for US domestic production and its energy strategy

Earlier this week I realised that output levels, and the profitability of production at these depressed price levels, was an interesting topic to look into since current oil prices appear too low to enable most producing countries and companies to operate profitably. Capital expenditure features heavily in that – meaning that, for a shale producer, can they justify – or even fund – the capex they need to keep their output stable or growing.

World Energy Investment from the IEA

The International Energy Agency (IEA) recently produced its annual assessment of World Energy Investment for 2020 (IEA 2020), just at the right time from my perspective, and it provides a lot of detail while making for a sobering read:

- Expectations are for a broad global recession with a U-shaped recovery leading to a loss of 6% of global GDP in 2020.

- Total energy investment will fall by 20% in 2020 because of Covid-19, from $1.9 bn to $1.5 bn

- The primary causes are both the sharp decline in energy revenues – especially in the oil sector – and the lockdowns imposed in many countries.

Spending cuts are expected to take place because of sharply lower demand, lower prices and lower earnings and we have already seen a number of companies rein in their capex budgets to reflect this. With large portions of the world population in lockdowns, there has also been significant disruption to investment activity.

Scenarios

While the IEA has produced a base case, which is downbeat and sobering, it does acknowledge that there are upsides and downsides to that. Much has been made, rightly I would say, of the downside risks of a second wave of the pandemic causing renewed lockdowns later this year and an even sharper fall in investment. I’d also say that we will see a considerable lag in the recovery of oil demand post-lockdown – ‘quickly in, slowly out’ Conversely, medical developments and economic actions may be more successful than currently assumed and these could potentially generate a faster and sharper recovery.

Outlook for different energy types

The demand shock has affected the oil sector most seriously, principally because of the effect of transport being dramatically curtailed. At its peak in early 2Q – when lockdowns were most widespread – 25% of oil demand disappeared and the annual impact is expected to be a decline of 9%, which the IEA notes will send demand back to levels seen in 2012. Most of the decline in oil investment – as opposed to oil demand – has been caused by lower revenues rather than the lockdowns. While that’s good for both emissions (forecast to decline by 8% this year) and the environment, I suspect nobody would have wanted to achieve that goal at the cost of 375,000 deaths around the world.

Gas has so far been relatively unaffected, showing just a 2% decline in 1Q, although that figure could rise over the rest of the year depending on how industrial and electricity demand develops over 2020.

Coal use is forecast to decline by 8%, largely on the back of a 5% decline in electricity use – although China’s recovery has a larger element of coal to it and may therefore shield the sector from the full 5% decline. Electricity demand has fallen by 20% as a result of the lockdowns which has resulted in gains for the renewables sector at the expense of coal, gas and even nuclear generation because of the relatively low cost of renewables and the preferential access afforded to renewables in many power systems.

What has happened is a rapid reversal of expectations: having anticipated an increase in energy investment of 2% this year, the reality is that we are now likely to see a fall of 20% instead. Within this, it looks as if oil – the fuel that has historically taken the largest share of consumer spending on energy – will cede that dominance to the second-placed energy, electricity. Capex in the oil and gas sector will likely decline by a third according to the IEA and perhaps by as much as a half or more in parts of the US shale sector. The Financial Times has noted that capital expenditure by the world’s nine largest oil and gas companies will fall by $38 bn, around the 20% figure estimated by the IEA.

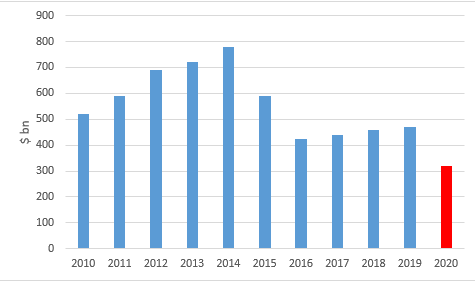

Global upstream capital expenditure

Upstream oil and gas spending

Upstream investment in the oil and gas sector fell sharply after the last oil price correction in 2014-15, with two successive years of falls of around a quarter in capex. 2020 is forecast to see a decline of 32% if the IEA’s numbers are correct. Normally lower prices stimulate demand and assist in the recovery – this time the lockdowns in most countries prevented this balancing mechanism from working so the industry faced just low prices without volume gains to shield revenues.

As a result, capex has suffered. A detailed analysis of investment plans by majors, NOCs and smaller players suggests that while the headline cut was 25%, the actual reduction could be as much as a third because of the difficulties in actually spending money on capex. While falling prices have in the past both pressured capex and encouraged cost savings, there is less fat to be cut this time round so lower capex may well translate into lower activity because capex is now in many cases the only effective route for many companies to cut costs.

The shale sector – where I started from – is particularly at risk. The financing environment for companies with relatively high-cost production – and an ongoing need for capital expenditure to maintain that production – deteriorated last year with investors wanting clear progress towards improved cash flow and profitability. The support sector for shale producers is also facing challenges, with the pressure on the shale producers being passed down the supply chain. Halliburton, for example, has cut its own capex by $400 mn, representing one-third of its originally planned $1.2 bn.

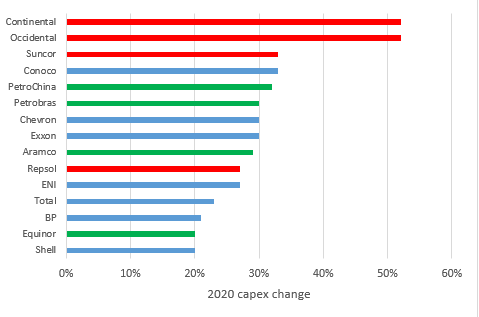

The chart below shows the revisions made to the initial capital expenditure plans for a range of companies: majors (in blue), NOCs (green) and independents (red). It’s fairly clear that some of the most stressed companies – at least judging by their cuts to capex plans for 2020 – are the independents with substantial exposure to the shale sector in the US. Shale basin capex has reportedly been cut from an original figure of $64.3 bn to just $35.3 bn in a series of cuts as prices declined precipitously.

Upstream spending cuts, 2020

US shale producers

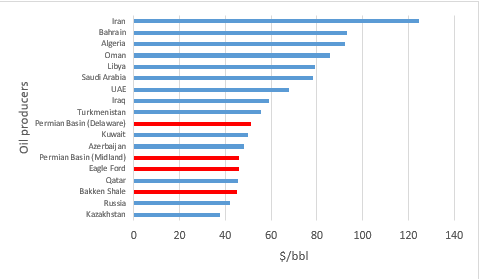

The shale producers are particularly at risk, since the breakeven price for much of their output is a WTI price of $45/bbl or above – and today that price is just above $35/bbl. In addition to losing money on each barrel, they are in many cases highly indebted. That has led to shale companies like Whiting Petroleum going into bankruptcy, while US lawyers say that seventeen companies have filed for bankruptcy – and I have no doubt more are coming, with some US analysts predicting as many as 250 bankruptcies by the end of 2021. On the gas side of the equation Tellurian, Sempra and Next Decade have all cut costs and postponed investment decisions so it seems unlikely that we’ll see any new North American LNG export approvals this decade. In the light of all this, access to capital will be tightened up by the lenders and it’s possible that some of the majors with deeper pockets will step in and acquire upstream assets from financially struggling independents which have gone bankrupt or which face the reality that they cannot cut costs fast or far enough to reach profitability, particularly in the shale sector.

Fiscal breakeven oil prices for producers

Overall impact on US domestic oil production

Unsurprisingly, overall US domestic oil output is falling more quickly than expected. The consultants Wood Mackenzie estimate that production had fallen by 2.3 mbd (around 20%) by late last month. The major shale basins of the Permian and Bakken (which need prices in the upper $40s to be profitable) were the source of most of the output loss. Standard Chartered suggest that output could fall by even more, 3 mbd lower than March while Goldman Sachs is apparently more optimistic, talking of just a 1.3 mbd decline in 2Q before a recovery. I guess it depends on your outlook for the oil price, but I’d be cautious about a price rise large enough to limit production declines to as little as 1.3 mbd – although there may be some light at the end of the tunnel in that my TS Lombard colleague Konstantinos Venetis highlights that some shale producers have managed to sell some of their stored crude into the price rally and we may actually see some pickup in their production.

Overall though that’s a poor outlook for a US energy strategy predicated on becoming a major exporter and no longer being dependent on imported energy with the problems that dependency brings.